We want to thank Certus for their guest blog. Part 1 in a 3-part series on the Laws of Nature for Information.

Every so often it is useful to stop and re-examine our previous ideas and understanding. When we considered some of the challenges faced by the Information Management Industry, that introspection proved to be quite revealing.

It turns out we don’t quite agree on what “information” really is. We’ve been using it for so long, albeit with a sense of confusion around its meaning. This blog post is the first in a three-part series revisiting what information is, what governs it and what the implications are to our Information Management practises as a result. Don’t worry – it’s not as dry as it may seem.

When we look around us, we tend to formulate consistent mechanisms to interpret and predict what we observe and interact with. We then express these things as law. To that end we’ve been quite prolific on establishing Laws of Nature that helps us to be successful in our everyday life. The notion of a law gives us a framework to understand what we are observing and predict the behaviour of what it will do in the future.

The law of nature is a set of principles that we hold fixed when we reason about the reality and when we encounter different situations. This is in contrast with generalisations. Generalisation as opposed to a law of nature is that a generalisation could be consistent, but an exception can occur.

So, what is a law of nature?

A law of nature is a precise statement based on discoveries through observation and experiments that have been repeatedly verified and never contradicted.

- Universally valid

- Do not vary in time

- Are very simple

- There areno exception

There are no excepts with a law of nature – that is what makes them so valuable.

So we have ample examples of Laws of Nature:

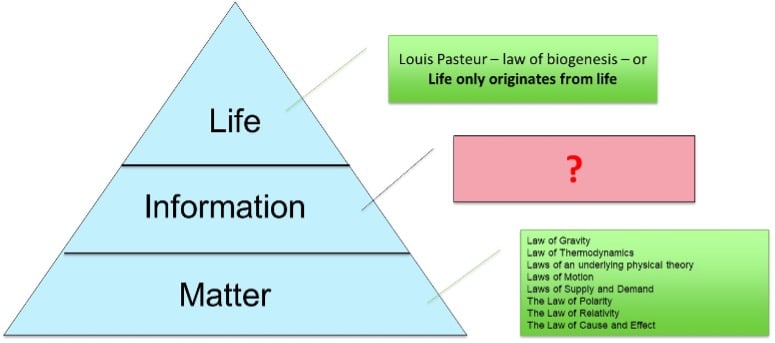

For matter we have copious amounts of laws of nature, laws of gravity, conservation of energy, laws of thermodynamics and many more.

The only law of nature for LIFE that has scientific backing (as per the emphasis above; precise, repeatable, never contradicted) was established by Louis Pasteur – law of biogenesis – or “life only originates from life”. There are lots of theories – indeed. The only scientific law thus far proven is from Pasteur.

For information, the definition and laws of nature for information is new. Wait, what? Yes, a recent development has information defined in a scientific frame as well as the accompanying laws.

Let’s apply a few tests first:

Irrespective of your persuasion – the following is reasonable to establish:

- We know that matter exist – that’s reasonably essential for our existence – readily observable.

- We know information exist – that’s also reasonably essential for our existence – readily observable (DNA)

- We know we are alive – that’s also reasonable essential to our existence – readily observable

So why the focus on laws of nature for information?

We’ve struggled with the definition of what information is. Struggled to really get a handle on when and where information exists. Take a robot for instance – gears, computers, and programming. If you weigh the robot, then delete the programming and weigh it again, is there any difference?

Norbert Wiener, an American mathematician said it quite succinctly:

“Information is information, neither matter nor energy.”

It’s a non-material entity. That is why we typically struggle with it, trying to apply the laws of matter to information. Therefore, as it does exist, we need to establish what laws of nature apply so we can work with it more effectively.

So, what is the scientific definition of information? In science, a definition must be very precise and very clear. For example: energy = force x distance. Scientific definitions of information are not just a single tag line. John Adams said:

“Facts are stubborn things; and whatever may be our wishes, our inclinations, or the dictates of our passions, they cannot alter the state of facts and evidence.”

So here is the slightly more complex but scientific definition of information, formulated by Dr Werner Gitt, a Professor of Engineering at Germany’s Physics-Technology Institute in Braunschweig, Germany.

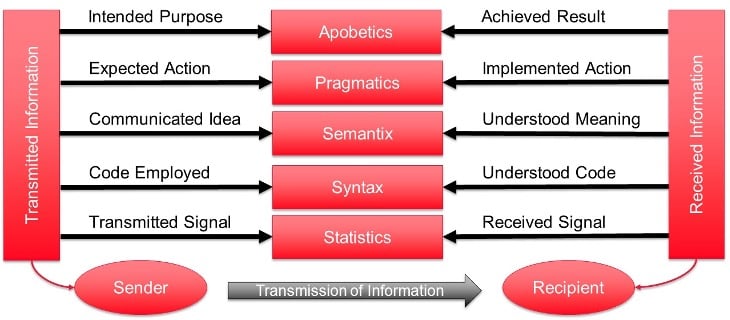

For information to exist, there must be a sender and a receiver available. What they exchange must have all five levels of requirements met to constitute information.

The 5 levels are:

- Statistics – consistent repeated use of the same symbol

- Syntax – sets of symbols expressed within constraints or rules for expression

- Semantics – the associated meaning of the code

- Pragmatics – the expected and implemented actions

- Apobetics – the purpose of the exchange of information

The complete characterisation:

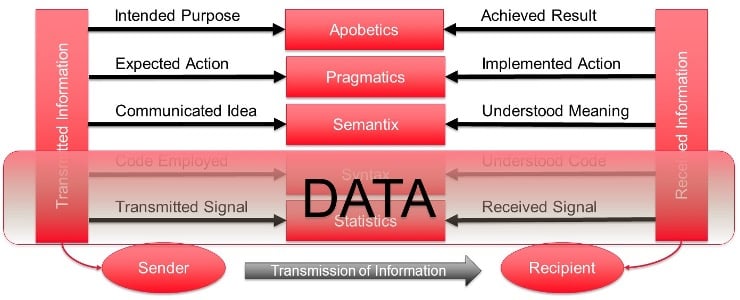

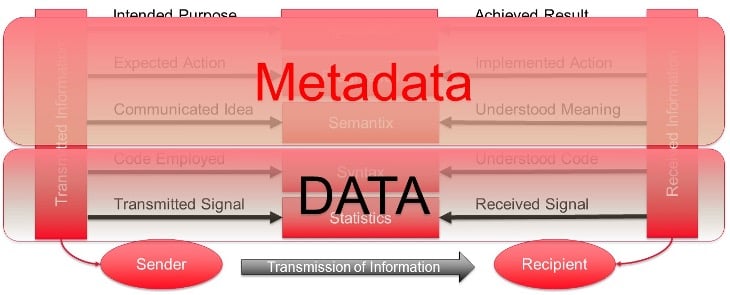

So why does this matter? Where does data then fit in? Where does metadata fit? Both these concepts we manage in the IM discipline. The below may shed some light on that.

Data is but the first two levels of the information requirement. That’s why we call things data warehouses.

As you can see, metadata constitutes the last three layers that form the levels required for information. This context is what really makes it valuable to the business and to the enterprise in general. Again, intuitively we’ve always insisted that metadata is important, yet we were unable to express why in such a succinct manner.

Now that we’ve defined information – let’s explore if there are Laws of Nature that apply to information. We’ll consider the implications to your Information Management practices and designs, and see how it applies to your Data Vault in time.

Recent Comments